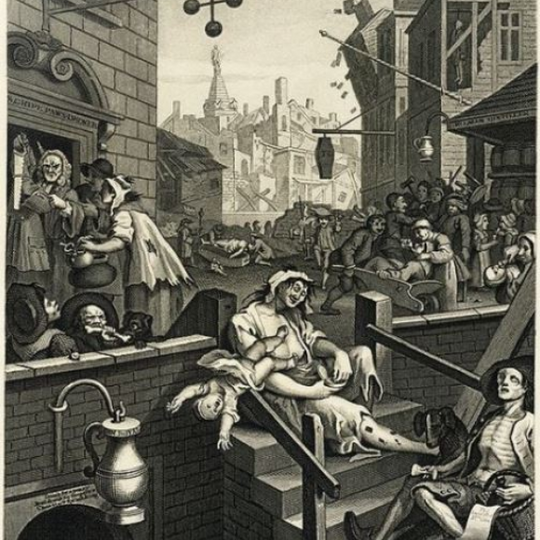

Image: William Hogarth’s Gin Lane (1751)

In the 16th Century, the Dutch created a medicinal alcohol using Juniper as the main ingredient. The name “Genever” derives from the Latin for juniper. This medicine was given to troops as part of their daily rations.

During the 17th century, Dutch troops fought alongside the English to ward off the attack of Louis XIV. The Dutch troops drank Genever heavily before going into battle and were deemed to be excessively brave. The English troops then decided to also drink Genever before going into battle and noted they had imbibed the Dutch’s courage hence the term “Dutch Courage”.

During the time of the war, English troops would take their Genever rations home with them and share it amongst their peers. The juniper flavoured spirit soon became vastly popular, especially with the poor. This was because just a few sips of water could kill you and the only other available drink was the vastly overpriced beer. The name ‘Genever’ was too much of a mouthful for some and was eventually shorted to ‘Gin’.

In 1689, King William III of Orange overthrew James II of England and became the King of England. The following year saw King William pass an act known as the ‘Distillers Act’, subsequently allowing the public to produce alcohol for free in their own home providing they passed a 10-day public notice, the law also restricted the importation of Brandy and wine.

This new law coupled with the taste for juniper flavoured spirits meant that pretty much anyone and everyone started producing juniper flavoured spirits. Unlike the Dutch, these spirits were not made using high quality grains to produce the spirit, they used low quality grain cut with mentholated spirits and turpentine which was then flavoured with locally grown juniper berries, anything else that was grown locally and natural sweeteners like liquorish root and rose water to mask the horrible flavours and make the gin more palatable. This was the start of a period that was known as the ‘Gin Craze’.

In 1720, the mutiny act was passed which stated that anyone who was distilling alcohol wouldn’t have to house soldiers in their home. These factors massively encouraged local gin production, so much so that in 1730 the number of gin shops in London exceeded 7000 which was one in every three public houses. By 1733, the average person was drinking 14 gallons of gin per annum, approx. 1.3 litres of gin per week. 1 in 3 structures in London produced or sold gin. At approximately 160 proof, this gin was highly intoxicating, not only was it strong but it wasn’t being sipped like a gin and tonic, in some cases it was being drank in vast quantities some were drinking around half a litre per day.

The gin obsession was blamed for misery, rising crime, madness, higher death rates and falling birth rates. Gin joints allowed women to drink alongside men for the first time and it is thought this led many women neglecting their children and turning to prostitution, hence gin becoming known as ‘Mother’s Ruin’.

The government was forced to take action. The 1736 Gin Act taxed retail sales at 20 shillings a gallon and made selling gin without a £50 annual licence strictly illegal. But over the next seven years, only two licences were taken out meaning reputable sellers were put out of business, and bootleggers thrived. Their gin, which went by colourful names such as ‘Ladies Delight’ and ‘Cuckold’s Comfort’, was more likely to have been flavoured with turpentine than juniper and was often poisonous, containing horrifying ingredients such as sulphuric acid.

In 1751, artist William Hogarth published his satirical print ‘Gin Lane’ (above) depicting disturbing scenes of gin-crazed London including a mother, covered in syphilitic sores, unwittingly dropping her baby while she takes a pinch of snuff. Aided by powerful propaganda such as this, the more successful 1751 Gin Act was passed. A change in the economy also helped turn the tide with a series of bad harvests forcing grain prices up, making landowners less dependent on the income from gin production. Food prices consequentially went up and wages went down, meaning the poor weren’t able to afford their drug of choice. By 1757, the Gin Craze was all but dead.